This essay was published in the Bowdoin Journal of Art in Spring 2021.

Introduction

On June 7, 1943, a letter to the editor by Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb was sent to the New York Times. Rothko’s The Syrian Bull and Gottlieb’s The Rape of Persephone had drawn criticism and confoundment from art critics. In the letter, Rothko and Gottlieb explained:

It is a widely accepted notion among painters that it does not matter what one paints as long as it is well painted. This is the essence of academicism. There is no such thing as good painting about nothing. We assert that the subject is crucial and only that subject matter is valid which is tragic and timeless. That is why we profess a spiritual kinship with primitive and archaic art.[1] [emphasis added]

As he grew into his mature style, Rothko spoke less and less about his art, preferring the works to speak for themselves. This letter presents a rare and striking insight into the artist’s thoughts about his work. In an early draft Rothko also says:

My own art is a new aspect of the same myth, and I am neither the first nor the last artist compelled to deal with the chimeras that seem the most profound message of our time.

The final letter was edited by fellow artist Barnett Newman, and in thanks Rothko and Gottlieb gifted Newman the two paintings.[2] Rothko, Gottlieb, and Newman were among artists in the early 1940’s to focus their work on classical mythological themes. As their letter shows, they believed their subject matter to be both meaningful and crucial to their own time period. By focusing on myths that were both tragic and timeless, they were able to express uniquely modern feelings of grief and impending doom through an archaic language of metaphors.

Rothko, Newman, and Gottlieb were deep thinkers as well as artists, and were conversant in artistic philosophy; their views at the time of this letter were heavily influenced by The Birth of Tragedy by Frederick Nietzsche. Analysis filtered through the Nietzschean lense yields a clearer understanding of their proclivity for the tragic and the resulting visual artwork from this period. Understanding this period of their art also allows for greater contextualization of their oeuvres. The use of explicitly tragic subject matter was a way for them to incorporate powerful, universal feelings in a more abstracted way in their mature work.

Tragedy was a fitting choice for inspiration during and following World War Two. Artists struggled with how to continue their practice while also every day learning about the horrors of war. As Barnett Newman articulated in 1966, the war made it seem nonsensical to paint men playing instruments or flowers. It demanded a radically new subject matter that grappled with the full reality of life.[3] Even more succinctly, he said “painting was dead.”[4]

As the art movement took hold, the painters of the New York School achieved acclaim and eventually acquired mythologies of their own. Rothko soon became a looming figure in the art world alongside the rising star Jackson Pollock. As they reached the height of their fame, both artists tragically died: Rothko committing suicide in his studio, and Pollock in a self-destructive alcoholic mania resulting in a car crash that killed himself and another person. The motif of the tragic artist seems almost as old as tragedy itself, and critics were quick to classify these artists accordingly.

Nietzsche proclaimed that the tragedy was the perfect expression of artistic sentiment in Classical Greece, and that it was perfectly suited for the modern world.[5] Following World War Two, the tragedy saw a rebirth in the form of abstract painting. This paper will examine works of art within a tragic framework as understood by Nietzsche and through a close examination of the original tragic plays from which they take inspiration.

Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy

In 1954, Rothko wrote that The Birth of Tragedy by Nietzsche had left an “indelible impression upon my mind and has forever colored the syntax of my own reflections in the questions of art.”[6] Written in 1870, this early work of Nietzsche’s discusses the history and theory of the tragic form. In The Birth of Tragedy, Nietzsche juxtaposed two aspects of art, represented by the spiritual energy of the gods Apollo and Dionysus. The Apollonian energy is that of the perfect and dreamlike: it is the impulse towards the ideal, and as such represents the god-like. The Dionysian, on the other hand, is the pure artistic force, unhinged and without limits.[7] To Nietzsche, these two forces are universally characteristic of the human condition, and they are the driving forces of art.

With its powerful chorus and raw expression of human pain through beautiful lyrics, Greek tragedy is the perfect union of both the Apollonian and Dionysian spirit. The expression of truly terrible aspects of humanity paired with the elegant lyricism of prose unites both the Apollonian and Dionysian, and allowed for spectators to at once recognize the pain of existence, but rejoice in its beauty. In this way it is the perfect example of art. Too much Dionysian energy and a work is painful, depressing, and drunkenly unhinged. Too much Apollonian and the result is a sterilized piece of academic work with no emotion behind it. The genius of the Greeks, to Nietzsche, was the synthesis of the two spirits, growing out of the state of “mystical self-abnegation and oneness.”[8]

This type of dialecticism was larger than just Nietzsche, too. Hegel, Marx, Schopenhauer, Heidegger, Rousseau, Kant, and even Freud all discuss a dialectic type of view of human history.[9] Ever since the French revolution, tragedy was manifested in a modern way as the struggle for resolution between opposing forces.[10] When viewed this way, modernity itself is tragic. If according to Nietzsche the tragic subject was the way to reconcile the two opposing forces of art, then it indeed seems attractive for artists in the crossroads between history and oblivion in the 20th century.

When Rothko, Newman, and Gottlieb began making tragic works in the 40’s they had lived through a heavy dose of tragedy themselves: when they reached adulthood the stock market crashed and the world economy came to a halt; they witnessed the rise of fascism in Europe and heard of the horrors of genocide; they read about the mass killing and threat of nuclear oblivion that came with the invention of the atomic bomb. After all this horror, Newman explained that the classical Apollonian style of painting simply would not do. How could one paint flowers and still lifes when they had lived through all of that? Faced with the Dionysian force of the truth about human cruelty, death, and utter destruction, but not satisfied with an Apollonian academic expression, the artists turned to the only subject matter that could possibly express their feelings: the tragic.

Aeschylus & Euripides: Rothko and the Expression of Tragic Loss

Rothko used the Tragedies of Aeschylus and Euripides to inspire his myth paintings in the early 40’s. In Euripides’s Iphigenia at Aulis, the King Agamemnon, as punishment for offending her, is forced by the goddess Diana to sacrifice his daughter, Iphigenia, in order to allow his fleet to safely sail to war. At first, he refuses, but then is convinced by his brother to allow the sacrifice. Under the guise of marriage to Achilles, Iphigenia and her mother Clytemnestra arrive at Aulis where the sacrifice is to take place. Once they learn of the plot, they are outraged at Agamemnon; but when Achilles reveals that the Greek army would be dangerously enraged if they could not fight, Iphigenia willingly sacrifices herself for the cause.[11]

The story of Iphigenia is one of a man who has to make a decision, torn between two sides, and in this way it is characteristically tragic. The Apollonian and Dionysian aspects are represented in numerous ways: the will of the gods vs. the human instinct to save family, the greater good vs. personal feelings, eternal honor in the eyes of the gods vs. worldly death. With its long sections of lyrical prose detailing the reasoning and logic of the characters, the Apollonian contends with the Dionysian force of the chorus expressing the feeling and emotions of the scenes in an intangible way.

In the context of all this, Rothko’s Sacrifice of Iphigenia, 1942 (fig. 1) presents these aspects in a unique pictorial language. On the left side is a figure understood to be Iphigenia, cloaked in a black cone-shaped garment, leaning away from a pair of arms that reach out from the right side. There is a duality between the black figure on the left and the lighter figure on the right, suggesting the tragic dialectic of Agamemnon’s choice. Iphigenia is cloaked, and thus her agency is reduced to being a mere pawn. Behind her are erratic figures, one of which is blood red and seems to have teeth, suggesting the bloodthirsty army that ultimately demanded her sacrifice.

Figure 1 (left): Mark Rothko, Sacrifice of Iphigenia, 1942, Collection of Christopher Rothko

Figure 2 (right): Timanthes, House of the Tragic Poet; Sacrifice of Iphigenia, 1st century CE, Fresco, Museo archeologico nazionale di Napoli

In his book The Laocoön: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry, Ephraim Lessing describes an ancient painting on the subject of Iphigenia by Timanthes (fig. 2). In that work, extreme grief and sorrow is depicted on the faces of the onlookers, except Agamemnon’s face is hidden. While there are competing theories about why the artist decided to cover the face, Lessing believes that the true expression on Agamemnon’s face would have been too hideous to include in the painting.[12] Thus, because beauty took precedence over communicating feeling, the pure spirit of tragedy in the myth is occluded by the Apollonian standards of art. When such standards of representation and beauty are eliminated and the subject is freed from those restraints, artists like Rothko are able to more easily communicate the tragic spirit.

As Rothko had stated, he did not aim to illustrate specific scenes from the myths, but rather the general, universal idea: while one may not relate to the specific situation of having to sacrifice one’s daughter, the idea of an impossible choice, the loss of an innocent life, and having to choose between something personal and something for the greater good can be felt by everyone. Following World War II, the pang of grief at the loss of an innocent life was just as palpable as it was in antiquity.

In a similar work, Rothko again visits the family of Iphigenia with The Omen of the Eagle (fig. 3), a work that according to him was based off of the Oresteia Trilogy by Aeschylus, but “deals not with a particular anecdote, but rather with the Spirit of the Myth, which is generic to all times.”[13] The Oresteia trilogy picks up after the sacrifice of Iphigenia: her mother, Clytemnestra plots and kills Agamemnon as revenge for the loss of their daughter. Then, their son Orestes plots to kill Clytemnestra for killing Agamemnon. Finally, the last play in the trilogy features Orestes put on trial for his crimes, which is meant to be the foundational mythology for the Athenian judicial system.[14]

A Nietzschean analysis of the myth reveals the two forces at play; the Dionysian aspect of the senseless murders and knowledge of human imperfection all concluded with an Apollonian solution to restore justice and order to the world.Through the trilogy the eagle serves as a symbol for Agamemnon: the impetus for the sacrifice of Iphigenia is the killing of a pregnant hare by two eagles, who symbolize Agamemnon and his brother Menelaus. In Agamemnon, the titular king and his brother are referred to by the chorus as “birds of war;”[15] and in the Libation Bearers, Orestes refers to Agamemnon as “the eagle father, of him who died in the twisting coils of the fearsome viper!”[16]

As a symbol for Agamemnon, the eagle, while successful in killing the pregnant hare and thus foreshadowing the victory in the Trojan war, also was a grim sign of the bloodshed to come. Particularly apropos for the time in which Rothko painted this work, the eagle in the Oresteia represents the inevitability of tragic bloodshed, warfare and innocent killing, which is quite prescient when one considers that the eagle was a symbol of both the United States and Germany. The central theme of revenge via murder is a timeless theme, the instigator of wars since the Trojan war and just as relatable in 1942.

Figure 3 (left): Mark Rothko, The Omen of the Eagle, 1942, oil and graphite on canvas, 142.558 x 243.84 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Figure 4 (right): Orestes, Electra, and Hermes at the Tomb of Agamemnon, ca. 350 BCE, Red figure pelike, height 430 mm, Musée du Louvre

Visually, the mutability of the figures in the work displays this universal nature of the spirit of the myth. The figures could be seen to represent any number of the characters from the play, or even a single character at various points of the story. As the trilogy goes on and the deaths stack up, they all begin to seem similar: revenge for murder is exacted in the form of murder. The tangled mass of limbs also evokes the tangled fates of the entire family, and when extrapolated, perhaps even all of humanity. The painting could also be read as featuring a tomb on the lowest level; when compared to a red figure pelike from ca. 350 BCE featuring Electra, Orestes and the god Hermes on the tomb of Agamemnon (fig. 4), compositional similarities can be seen with the space vertically organized and figures occupying a higher register with architectural tomb-like features on the lower portion. Rothko adapts not just the theme, but compositional influences from antiquity.

Sophocles and the Tragic Hero

Sophocles is known for introducing the chorus as a third character to the tragedy. This innovation allows for the complexity of seeing the main character from different points of view, and it also increased the influence of the chorus on the play and accordingly increased the influence of the Dionysian.[17] In his plays there is a sense of heightened drama and narrative intricacy, which perfectly suited the story of Oedipus.

The King Oedipus is perhaps the most referenced tragic figure from antiquity. While perhaps most known for the Freudian complex of which he is the namesake, according to Nietzsche, Oedipus was a noble man who was tragically destined to a terrible fate due to his search for understanding.[18] In the Sophoclean play Oedipus Tyrannus, Oedipus is prophesied to kill his father and marry his mother. In an attempt to evade the prophecy, he is ordered to be killed as an infant, but is instead secretly raised by another couple. He then unknowingly encounters and kills father, then solves the riddle of the Sphinx and marries the widowed queen Jocasta, who was actually his mother. When they find out about the truth, Jocasta commits suicide and Oedipus blinds himself. The tragedy in Oedipus’s tale lies in the lack of agency he has, and that he is relegated to a mere pawn of the gods at his birth with no hope of redemption.[19]

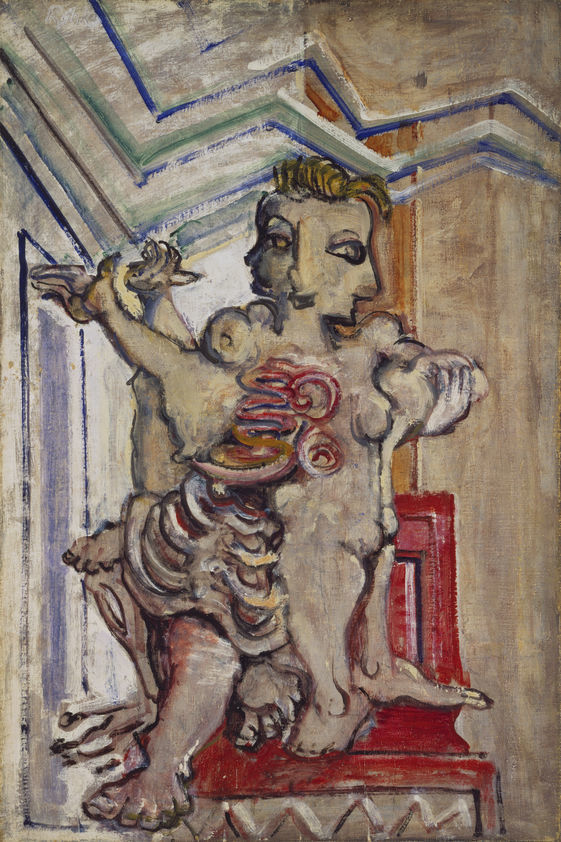

The character of Oedipus has been visited by many artists. In 1940 Rothko completed a work based on the myth, with a morphing of limbs similar to his Omen of the Eagle. In Oedipus (fig. 5) male and female tangle and merge into one, suggesting the incestuous relationship between Oedipus and Jocasta. Like in his other myth paintings Rothko includes a classical-inspired background, featuring geometric shapes, echoing columns and walls. The pristine permanence of the columns behind the confusing chaos of the figure communicates tragedy in that it sets a Dionysian element in front of an Apollonian one. The tension between order and chaos compositionally and thematically balances the work.

Figure 5: Mark Rothko, Oedipus, 1940, oil on linen, 36 x 24 inches, Collection of Christopher Rothko

Adolph Gottlieb also visited the subject of Oedipus, focusing on different aspects of the tragic myth. In Eyes of Oedipus (fig. 6) Gottlieb paints what he called a pictograph, which was described by Barnett Newman as a “series of fragmentary pictures to be united in the mind of the onlooker just as impressionist color is united.”[20] Newman explains that the dominant theme of Gottlieb’s work is the tragedy of life:

Man is a tragic being, and the heart of this tragedy is the metaphysical problem of part and whole. This dichotomy of our nature, from which we can never escape and which because of its nature impels us helplessly to try to resolve it, motivates our struggle for perfection and seals our inevitable doom.[21]

Notice the inherently Nietzschean language Newman uses, describing tragedy arising from conflict between two opposing forces. He goes on to explain that the pictograph form communicates this contentious relationship between symbols. The disparate parts mimic the “insoluble dilemma” that is the tragedy of humanity. In Eyes of Oedipus the pictograph form is clear, and indeed each part seems to struggle to break out of its geometric boundaries created by Gottlieb, and they conflict with each other.

Thematically, the focus on not only Oedipus but the eyes of Oedipus is key to the work. Unlike where Rothko based his works on entire plays, or even trilogies, Gottlieb chose one specific element of the myth to focus on. The surrealists had often used the eye motif to represent the inner vision, but here Gottlieb uses it to show the feelings of guilt central to Oedipus’s story.[22] The metaphor of sight is repeated throughout Oedipus Tyrannus. When Oedipus finds out he had accidentally fulfilled the prophecy, he says: “Oh, Oh! All is now clear! O light, now I look on you for the last time, I who am revealed as cursed in my birth, cursed in my marriage, cursed in my killing.”[23] Then the chorus, with its raw energy of musical expression, laments about Oedipus’ fate, saying that Oedipus himself is an example of the tragedy of human existence, and that “time the all-seeing has found you out against your will.”

Then the chorus tells how Oedipus discovered his wife, now revealed to also be his mother, after she had committed suicide after learning the truth:

And when he saw her, with a fearful roar, poor man, he untied the knot from which she hung: and when the unhappy woman lay upon the ground, what he saw next was terrible. For he broke off the golden pins from her raiment, with which she was adorned, and lifting up his eyes struck them, uttering such words as these: that they should not see his dread sufferings or his dread actions, but in the future they should see in darkness those they never should have seen, and fail to recognise those he wished to know. Repeating such words as these he lifted up his eyes and not once but many times struck them; the bleeding eyeballs soaked his cheeks, and did not cease to drip.[24]

That the chorus conveyed this section of the story heightened the emotional drama and pure Dionysian spirit of the story. Sight is used as a metaphor for learning the terrible truth of existence: once Oedipus “sees” the truth it is so unbearable that he literally blinds himself. The eyes in Gottlieb’s pictograph are in varying states: some stare back out at the viewer, some are seen in profile, some are dripping with hot pink-red blood. Vision as a subject in a piece of visual art is also inherently self-reflexive; as the viewer gazes at the painting, multiple eyes gaze back, redirecting the question of guilt and the perils of seeing back at the viewer. Gottlieb even recognized that the viewer played an integral part in these pictographs. He left them purposely looking a bit unfinished, with the hopes that as the viewer became engaged in the work, they would complete it and the work would bring them to “the beginning of seeing.”[25]

Figure 6 (left): Adolph Gottlieb, Eyes of Oedipus, 1945, oil on canvas, 91 x 70 cm, The Israel Museum

Figure 7 (right): Adolph Gottlieb, Hands of Oedipus, 1943, Oil on linen, 40 x 35 15/16"

Gottlieb focuses on a slightly different element of the same scene in The Hands of Oedipus (fig. 7). This work is also in the pictograph form, also communicating the tragic fragmentary aspect of the world. Instead of just focusing the eyes, this work also features hands, which communicate a whole other aspect of the Oedipus myth: agency, and lack thereof. While the eyes merely represent sight and truth, the hands are symbols of his own actions: it was with his hands that he killed his father, his hands that he acted with his mother, and his hands that he blinded himself. This focus on agency emphasizes the fact that while Oedipus was a victim of circumstance, he did indeed commit terrible actions. It is at once a recognition of man’s free will yet a condemnation of the terrible actions that we choose to enact. In the work, the hands point in different directions, appearing to shift the blame. They point to different faces, and on one section on the left, one hand points directly to Oedipus’s eyes. While Oedipus did have reason to blame others for his circumstances, in the end he was the one who acted, and thus in the end, he commits the act of blinding himself. While it is perilous to extract a political message from this work to the contemporary times, it is safe to say that themes of agency, terror, understanding, atrocity, warfare, and leadership were all salient themes in 1943.

While Nietzsche cast Oedipus as an innocent man, he was still doomed because of his search for truth; in this way Oedipus can be seen as a figure similar to the 20th century artist: struggling to do the right thing yet doomed due to circumstances beyond their control.

Transitions to Abstract Expressionism

Cleary Rothko and Gottlieb were both conversant in Greek Tragedy, as they drew their inspiration from specific characters and motifs from the writings of Sophocles, Euripides and Aeschylus. They were not the only ones interested in the myth, however. Other artists like Barnett Newman, Jackson Pollock, Arshile Gorky, Helen Frankenthaler, and more of their contemporaries abstracted themes and motifs from mythology. Many used stories and characters that, while not strictly from a tragic play, were tragic figures in that they suffered unfortunate fates, often due to circumstances out of their control.

The use of the tragic with its Apollonian and Dionysian aspects fostered the transition to a new art form. Sometimes called Abstract Expressionism, or the New York School of painting, this movement rejected the use of figures and forms and instead pushed for the primacy of shape, color and gesture as a means of personal expression. These artists rejected the academicism of technique and instead gravitated towards pure feeling. This shift, I would argue, is one from the pure Apollonian to a greater emphasis on the Dionysian, and as such the tragic paintings were a crucial bridge between the two. As students of philosophy and mythology, many of them were conscious of this shift and also interpreted it in mythological terms: in 1949, now in his mature style, Barnett Newman’s only mythological-titled piece was called Dionysius (fig. 8), perhaps in an ode to the creative spirit he had been enjoying.[26]

Figure 8: Barnett Newman, Dionysius, 1949, oil on canvas, 175.26 x 121.92 cm

This is not to say that the artists completely rejected the Apollonian; as Nietzsche explained, the Apollonian is an ever-constant force in art. Indeed, one common theme amongst the New York artists is a sense of dialectic struggle between order and chaos.[27] One example of this would be Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings, like No. 1, 1950 (Lavender Mist) (fig 9). To the casual observer they may seem like complete chaos, like someone had simply spilled paint all over a canvas and called it a painting post-hoc. Pollock, however, was insistent that his works were intentional. Still, the emotional force of the gesture conveys a much stronger Dionysian aspect than traditionally academic painting.

Jackson Pollock embodied the Dionysian spirit in every aspect of the term. He rejected the form and made his pure artistic force the subject of his works. Deeply concerned with the introspective and psychological, he believed that art should be an expression of one’s innermost feelings. When told to paint from nature, he famously replied “I am nature.”[28] Gazing at a Pollock one can feel the sheer energy of movement and feeling; very much like the chorus from a tragic play, it may move the observer in a way that they cannot even articulate.

Figure 9: Jackson Pollock, Number 1, 1950 (Lavender Mist), 1950, oil, enamel, and aluminum on canvas, 221 x 299.7 cm (87 x 118 in.), National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

This phenomenon, of extracting an emotional reaction without any clear visual cue or illustration, was also a key feature of both Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman’s works. Rothko’s mature work features gigantic, lushly painted fields of color that appear to float off the canvas. A Rothko is not merely a painting, but an experience in itself. In this way Rothko as well learned to express a Dionysian spirit free from the confines of Apollonian rules. While in 1943 Rothko professed to be reaching the “Spirit of the Myth,” by glancing at his mature works it seems that he truly achieved this spirit with his color fields, many years later. For example, his No. 61 (Rust and Blue) (fig. 10) provokes feelings of sadness, anguish, and tragedy simply through its use of color and rich yet thinly painted layers. This work would not have been possible, however, without his earlier mythological paintings to give him the technical and philosophical foundation to simplify his work and enter into the world of pure abstraction. Perhaps summarized best by Rothko: “we favor the simple expression of the complex thought.”[29] While conferring him an honorary doctorate in 1969, Yale University’s statement of Rothko’s mature work stated “Your paintings are marked by a simplicity of form and a magnificence of color. In them you have attained a visual and spiritual grandeur whose foundation is the tragic vein in all human existence”[30]

Figure 10: Mark Rothko, No. 62 (Rust and Blue), oil on canvas, 115 1/4 x 92 x 1 3/4 in. (292.74 x 233.68 x 4.45 cm), The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

The Tragic Artist

With its emphasis on the personal and performative, it is not surprising that such a focus on Dionysian aspects of art was subsumed into the artists themselves. The perennial motif of the “tragic” artist was especially rampant amongst the Abstract Expressionists. Their living conditions were notoriously squalid; art critic Clement Greenberg famously observed, “Their isolation is inconceivable, crushing, unbroken, damning. That anyone can produce art on a respectable level in this situation is highly improbable.”[31] As these artists improbably gained success, they gained mythologies of their own.

Jackson Pollock was perhaps the biggest mythic figure to arise from this period. His origin from Cody, Wyoming and rough cowboy-like demeanor garnered interest as soon as he stepped into the New York art scene. From there, his grandiose paintings and breakthrough drip technique, combined with his penchant for alcohol and manic episodes made him a figure larger-than-life. His life ended tragically, yet unfortunately in a way that many had almost seen coming, in a car crash on Long Island during a drunken rampage. Shortly after his death, in 1958 artist Alan Kaprow wrote that while the idea of a tortured artist was well known through the likes of Van Gogh and Rimbaud,

But now it was our time, and a man some of us know. This ultimate sacrificial aspect of being an artist, while not a new idea, seemed in Pollock terribly modern, and in him the statement and the ritual were so grand, so authoritative and all-encompassing in their scale and daring that that, whatever out private convictions, we could not fail to be affected by their spirit.[32]

If one did not know who was being discussed, Kaprow’s language could be mistaken for being about a figure straight out of a Sophoclean play. Pollock truly was a tragic figure. In his own life he battled true demons, struggling with alcoholism and mental health problems; it is also no coincidence that Dionysus, while representing creativity, was also the god of wine mania and drunkenness. The Apollonian force in his life, art, did fight back. It was during the four years of his sobriety that Pollock produced some of his most successful works. The struggle between order and chaos was so clear in Pollock’s life that it makes perfect sense that on the occasion of his death people were quick to label him as another example of a tragic artist.

Pollock was not the only one of his generation of artists to receive such eulogizing. Upon the suicide of artist Arshile Gorky in 1948, Barnett Newman wrote of Gorky as an example of the passionate and futile life of the artist. “While the futility of an artist’s act gives him his strength, at the same time it intensifies the tragedy of his life above the normal tragedy of other men,” he says. “Gorky’s life would have been tragic in any country and in any society.”[33] Rothko, too, ultimately suffered a tragic fate. Two years after suffering from an aneurysm, weakened by medications and severely depressed, he committed suicide in his studio by overdosing on barbiturates and slashing his arms.[34]

Of course, suicide does not inherently and exclusively make an artist a tragic one. Rather, as Newman put it, there is an essence of tragedy inherent to being an artist. While the Dionysian and Apollonian battle amongst themselves in art, they are also dominant forces in the life of an artist. The Dionysian compels an artist to create, and whispers to them the primal, ancient, and essential truth of things. The constrictions of the academic world and social opinions of what art is and what art should be were the Apollonian forces that the artists of the New York school fought to break out from. When an artist becomes subsumed with the Dionysian, they are susceptible to becoming overwhelmed with the feeling. As Nietzsche said, the tragic hero “takes the entire Dionysian world on his shoulders and disburdens us thereof.”[35] Like Oedipus, when one spends enough time searching for the truth, sometimes the result is unbearable.

Conclusion

In order to tell existential truths about humanity while also creating beautiful art, the ancient Greeks invented the form of the tragic play. Nietzsche outlined the two main elements of tragedy and proclaimed that they were apt for application in modern art: “Dare now to be tragic men, for ye are yet to be redeemed!” he urged the artist. “Equip yourselves for severe conflict, but believe in the wonders of your god!”[36]

Mark Rothko, Adolph Gottlieb, Barnett Newman and their contemporaries took up Nietzsche’s challenge and created paintings that dealt with existential turmoil by combining the Apollonian and Dionysian and drew inspiration directly from the tragic plays of antiquity. By doing so, they gained a deeper understanding of what the tragic truly is, and this impulse propelled them to their mature art styles- changing drastically in form but retaining the essential mythological spirit. Unfortunately, a few of them truly did dare to be tragic men and suffered the ultimate tragic fate. Following their deaths, both Rothko and Pollock were transformed by the art world into mythical entities of their own, to the point where stories and tall tales about their lives occlude the real meaning of the artwork.[37]

The connection between art and tragedy cannot be overstated. While art has an aesthetic quality that invites admiration, it also has the power to move us emotionally; the synthesis of these two feelings is precisely what Nietzsche was articulating. It should never be forgotten that the true essence of mythic tragedy is the same across time and culture. The Greeks, Nietzsche, the New York artists and even the media who made myths out of Pollock and Rothko are all engaging in and creating stories around the same essential truth about humanity; and that truth is timeless and tragic.

[1] Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb, “Rothko and Gottlieb’s letter to the editor, 1943” Writings on Art ed. Miguel Lopez-Remiro, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), 36.

[2] Clearwater, Bonnie. "Shared Myths: Reconsideration of Rothko's and Gottlieb's Letter to The New York Times." Archives of American Art Journal 24, no. 1 (1984): 23-25. Accessed December 6, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1557346.

[3] Barnett Newman, “A Conversation: Barnett Newman and Thomas B. Hess” in Barnett Newman, Selected Writings and Interviews, ed. John P. O’Neil, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1990), 274-75.

[4] Barnett Newman, “Interview with Emile de Antonio” in Barnett Newman, Selected Writings and Interviews, ed. John P. O’Neil, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1990), 302.

[5]Friederick Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy or Hellenism and Pessimism, ed Oscar Levy, trans William August Haussman. (Urbana, Illinois: Project Gutenberg, 2016) 129-130 Retrieved December 9, 2020 from https://www.gutenberg.org/files/51356/51356-h/51356-h.htm

[6] Mark Rothko, “Whenever one begins to speculate, ca. 1954” Writings on Art ed. Miguel Lopez-Remiro, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), 109.

[7] Nietzsche, Birth of Tragedy, 20-22.

[8] Ibid, 46.

[9] Vincent Lambropoulos, The Tragic Idea, (London: Gerald Duckworth & Co: 2006), 7-9.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Euripides, Iphigenia at Aulis, ed and trans David Kovacs, Loeb Classical Library 495. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003), lines 80-110.

[12] Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, The Laocoön: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984), 16-7.

[13] Mark Rothko, “Comments on The Omen of the Eagle, 1943” Writings on Art ed. Miguel Lopez-Remiro, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), 41.

[14] H.D.F. Kitto, “The Oresteia” Greek Tragedy, (New York: Routledge, 1939), 120-58..

[15] Aeschylus. Oresteia: Agamemnon, ed and trans Alan H. Sommerstein, Loeb Classical Library 146. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), line 50

[16] Aeschylus, Oresteia: Libation-Bearers, ed and trans Alan H. Sommerstein, Loeb Classical Library 146. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), lines 240-50.

[17] H.D.F. Kitto, Greek Tragedy, (New York: Routledge, 1939), 245.

[18] Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy, 73.

[19] H.D.F. Kitto, Greek Tragedy, 225

[20] Barnett Newman, “The Painting of Tamayo and Gottlieb,” in Barnett Newman, Selected Writings and Interviews, ed. John P. O’Neil, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1990), 76.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Judith Bernstock, "Classical Mythology in Twentieth-Century Art: An Overview of a Humanistic Approach," Artibus Et Historiae no. 27 (July 1993), 173-4.

[23] Sophocles, Oedipus Tyrannus, ed and trans Hugh Lloyd-Jones, Loeb Classical Library 20 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994), lines 1180-85.

[24] Sophocles, Oedipus Tyrannus, lines 1264-77.

[25] “Making Art in Challenging Times: Gottlieb’s Pictographs” Adolph & Esther Gottlieb Foundation, July 2020, retrieved from https://www.gottliebfoundation.org/blog/2020/7/1/making-art-in-challenging-times-gottliebs-pictographs on December 9, 2020.

[26] Bernstock, "Classical Mythology in Twentieth-Century Art: An Overview of a Humanistic Approach, 168.

[27]Alicja Kępińska and Patrick Lee, “Chaos as a Value in the Mythological Background of Action Painting,” Artibus et Historiae Vol. 7, No. 14 (1986), pp. 107-123, 121.

[28] David Anfam, “An Unending Equation” in Abstract Expressionism ed David Anfam, (London: Royal Academy of Arts Publications, 2016), 25.

[29]Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb, “Rothko and Gottlieb’s letter to the editor, 1943” Writings on Art ed. Miguel Lopez-Remiro, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), 36.

[30] Miguel Lopez-Remiro, footnote in “Acceptance of Yale University honorary doctorate, 1969,” in Writings on Art ed. Miguel Lopez-Remiro, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), 157.

[31] Clement Greenberg, “The Present Prospects of American Painting and Sculpture” Horizon (October 1947).

[32] Allan Kaprow, “Legacy of Jackson Pollock,” in Essays on The Blurring of Art and Life ed. Jeff Kelley, (London: University of California Press, 2003), 2.

[33] Barnett Newman, “Arshile Gorky: Poet and Immolator” in Barnett Newman, Selected Writings and Interviews, ed. John P. O’Neil, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1990), 112.

[34] Miguel Lopez-Remiro, Chronology in Writings on Art ed. Miguel Lopez-Remiro, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), 168.

[35] Nietzsche, Birth of Tragedy, 160.

[36] Ibid., 157.

[37] For more on this, see: Mancusi-Ungaro, Carol C, “On Myth and Physical Fact.”

Getty Research Journal; 2017 Supplement, Vol. 9 Issue S1, p111-116.

Comentarios